Big Tobacco's decisive defeat on plain packaging laws won't stop its war against public health

- Written by Genevieve Wilkinson, Lecturer in Intellectual Property and Human Rights, University of Technology Sydney

After a decade of legal challenges by the tobacco lobby, Australia’s pioneering push to eliminate all tobacco advertising finally has clear air.

Its longest stoush, over plain packaging laws introduced in 2012, finally ended last month, when the highest adjudicative body of the Word Trade Organisation affirmed a 2018 ruling the laws did not constitute an effective trade barrier or infringe tobacco companies’ trade mark rights.

This is a significant win. But the global war is far from over. While this decision should encourage more countries to introduce plain packaging, the tobacco lobby can still be expected to use legal chicanery to thwart such public health measures.

Read more: Australia's decisive win on plain packaging paves way for other countries to follow suit

Eliminating tobacco advertising

Australian rugby league’s Winfield Cup, awarded to grand final winners from 1982 to 1995. Winfield’s use of the sport to promote its products ended with federal laws prohibiting such advertising.

National Library of Australia

Australian rugby league’s Winfield Cup, awarded to grand final winners from 1982 to 1995. Winfield’s use of the sport to promote its products ended with federal laws prohibiting such advertising.

National Library of Australia

Australia’s tobacco plain packaging laws were a world first – the final step in a national preventative health strategy to deter smoking by eliminating all avenues for tobacco promotion.

It followed Australia banning cigarette advertising on radio and television in 1976, banning the broadcast or publication of any form of tobacco promotion (such as through sponsorship of sports) in 1993, requirements for text-only health warnings on tobacco products in 1995, and warnings featuring graphic images of smoking health impacts in 2006.

Branding on packaging was seen as the last avenue for tobacco companies to market their products to smokers.

The plain packaging laws banned all distinctive branding elements on packets. All products had to use the same drab brown colour found by research to be the least appealing.

Only “word marks” identifying the source and type of tobacco product, such as Marlboro Gold or Champion Ruby, were permitted.

Australia’s uniform tobacco plain packaging, introduced in 2012.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Australia’s uniform tobacco plain packaging, introduced in 2012.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Legal challenges to Australia’s law

The tobacco lobby sought to thwart the Australian law through a variety of legal challenges.

British American Tobacco and Japan Tobacco International took action in Australia’s High Court. They argued the law was an unconstitutional acquisition of their intellectual property rights in their brands. The High Court conclusively rejected this in October 2012.

Phillip Morris reorganised its legal structure to seek compensation as a Hong Kong company under provisions of the 1993 Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement between Australia and Hong Kong. This gambit failed in 2015.

The WTO case was initiated in 2013 by tobacco exporters Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Indonesia and the Ukraine, with tobacco industry help. They argued Australia had restricted trade and trade mark use more than needed to protect public health, contravening international trade rules.

The WTO rejected these arguments in 2018. Its Appellate Body affirmed that decision on June 9, rejecting the appeal by Honduras and the Dominican Republic.

Read more: Coronavirus: big tobacco sees an opportunity in the pandemic

Trade mark arguments

The Appellate Body ruled plain packaging was a legitimate part of Australia’s comprehensive range of tobacco control measures and did not amount to a restriction on trade.

It rejected the argument Australia had infringed trade mark rights under the 1995 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (known as TRIPS), binding on all 164 WTO member nations.

It affirmed TRIPS granted a trade mark owner “the exclusive right to preclude unauthorised third parties from using identical or similar signs”. But it said there was no “positive right” to use a trade mark, as the appellants argued.

Nor did plain packaging laws contravene section 20 of the TRIPS rules, which states trade mark use “shall not be unjustifiably encumbered by special requirements”. Member nations “enjoy a certain degree of discretion in imposing encumbrances on the use of trademarks”, the Appellate Body said.

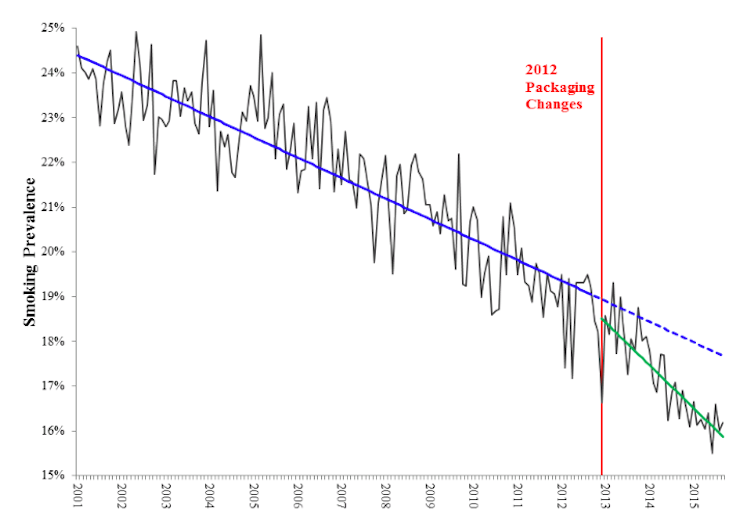

It agreed Australia’s policy was supported by the public health objectives and evidence, including a 2016 review showing reduced smoking rates.

Impact of plain packaging on smoking prevalence in Australia

Study of the impact of the tobacco plain packaging measure on smoking prevalence in Australia. 2016.

Tasneem Chipty/Roy Morgan, CC BY-SA

Study of the impact of the tobacco plain packaging measure on smoking prevalence in Australia. 2016.

Tasneem Chipty/Roy Morgan, CC BY-SA

It also noted Australia’s obligations to reduce smoking as a signatory to the World Health Organisation’s 2003 Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. The convention’s guidelines recommend “measures to restrict or prohibit the use of logos, colours, brand images or promotional information on packaging”.

Global battle will continue

So this is a comprehensive vindication of Australia’s leadership on tobacco packaging. It should encourage other nations to follow suit. More than ten have already done so. The latest is Singapore, where plain packaging laws came into effect on July 1.

But don’t expect Big Tobacco to stop using litigation and other tactics to deter nations following suit.

Defending Phillip Morris’ Hong Kong gambit, for example, cost Australia about A$50 million in legal fees. Researchers have suggested the threat of legal action using trade deals delayed New Zealand’s introduction of tobacco plain packaging laws by years.

For poorer nations such costs are an even greater deterrent. Uruguay, for example, won its six-year plain-packaging battle with Phillip Morris only with aid from US billionaire Michael Bloomberg.

Read more: China's tobacco industry is building schools and no one is watching

Ferrari teammates Fernando Alonso and Felipe Massa at the Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix in Melbourne, Australia, in March 2010. The racing team was accused of using ‘subliminal’ tobacco advertising for the Marlboro brand in exchange for a US$1 billion sponsorship deal.

Diego Azubel/EPA

Ferrari teammates Fernando Alonso and Felipe Massa at the Australian Formula 1 Grand Prix in Melbourne, Australia, in March 2010. The racing team was accused of using ‘subliminal’ tobacco advertising for the Marlboro brand in exchange for a US$1 billion sponsorship deal.

Diego Azubel/EPA

Tobacco companies also have a history of using other means to get their way. In South Africa in 2017, for example, British American Tobacco threatened to close its local cigarette factory if the government pursued plain packaging laws.

Read more: The next battles against tobacco must be fought in the world’s major cities

With about 80% of the world’s 1.3 billion smokers living in low and middle income countries, we can expect tobacco interests to rely on their financial might, if not their legal right, to defend their profits.

Their war against the human right to health will continue.

Authors: Genevieve Wilkinson, Lecturer in Intellectual Property and Human Rights, University of Technology Sydney