The floods affecting Australia’s eastern seaboard are a “1 in 1,000-year event”, according to New South Wales Premier Dominic Perrottet. But that’s not what science, or the insurance industry, suggests.

Throughout Australia in areas prone to fires, cyclones and floods, home owners and businesses are facing escalating insurance costs as the frequency and severity of extreme weather events increase with the warming climate.

Premiums have risen sharply over the past decade as insurers count the cost of insurance claims and factor in future risks. The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, published this week, predicts global warming of 1.5℃ will lead to a fourfold increase in natural disasters.

Rising insurance premiums are creating a crisis of underinsurance in Australia.

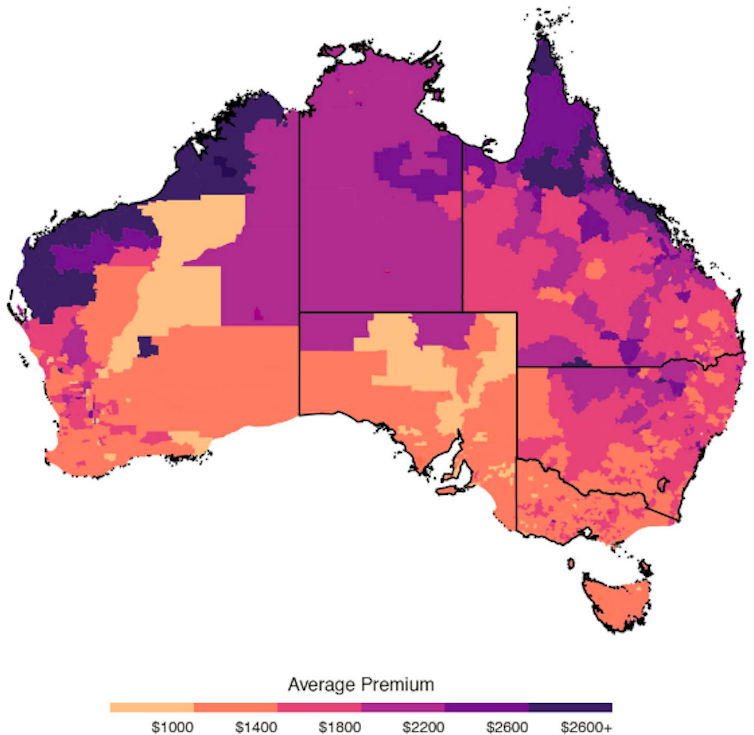

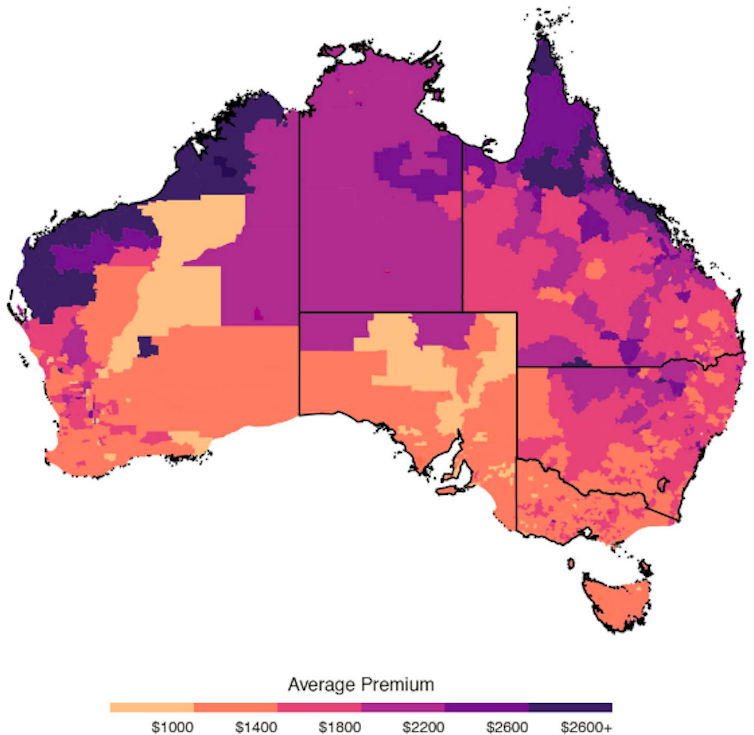

In 2017 the federal government tasked the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to investigate insurance affordability in northern Australia, where destructive storms and floods are most common. The commission delivered its final report in 2020. It found the average cost of home and contents insurance in northern Australia was almost double the rest of Australia – $2,500 compared with $1,400. The rate of non-insurance was almost double – 20% compared with 11%.

Average premiums for combined home and contents insurance, 2018–19

ACCC analysis of data obtained from insurers., CC BY

While the areas now experiencing their worst flooding in recorded history aren’t part of the riskiest areas identified by the insurance inquiry, the dynamics are the same.

Those not insured or underinsured will be financially devastated. Insurance premiums will rise. As a result, more people will underinsure or drop their insurance completely, compounding the social disaster that will come with the next natural disaster.

So, what do about it?

Tackling insurance affordability

There are two main ways to reduce insurance premiums.

One is to reduce global warming. Obviously this is not something Australia can achieve on its own, but it can be part of the solution.

The other is to reduce the damage caused by extreme events, by constructing more disaster-resistant buildings, or not rebuilding in high-risk areas.

The federal government, however, has put most of its eggs in a different basket, with a plan to subsidise to insurance premiums in northern Australia.

A sign of floods present and past in Chinderah, northern NSW, on March 1 2022.

Jason O'Brien/AAP

This won’t do much for those affected by the current floods. It won’t even do much to solve the insurance crisis in northern Australia.

The reinsurance pool, a blunt tool

In the 2021 budget the federal government committed A$10 billion to a cyclone and flood damage reinsurance pool, “to ensure Australians in cyclone-prone areas have access to affordable insurance”. The legislation to establish this pool is now before parliament.

The ostensible rationale is that the government can drive down insurance costs for consumers by stepping in and acting as wholesaler in the reinsurance market, in which insurers insure themselves against the risk of crippling insurance payouts.

The idea is that discounted reinsurance will lead insurers to lower their premiums.

Read more:

A national insurance crisis looms. The Morrison government's $10 billion 'pool' plan won't fix it

There is no guarantee, however, that insurers will pass on their cheaper costs to customers. This means the benefits of the pool are unclear.

So are its costs. Effectively, the government is shifting risk from insurers to itself, subsidising insurance premiums for those in some parts the country from the public purse.

The ACCC inquiry gave considerable attention to the idea of a reinsurance pool. While acknowledging there could be some benefits, it concluded the risks outweigh the rewards:

We do not consider that a reinsurance pool is necessary to address availability issues in northern Australia.

Targeting and mitigating

Above and beyond the aforementioned problems, there are two telling failures of the reinsurance pool plan.

First, subsidising insurance companies doesn’t target help to those who need it most: low-income households.

There is a growing body of research showing that natural disasters, and the ways governments respond to them, is contributing to greater inequality.

As the South Australian Council of Social Service makes clear in a report published this week, improving insurance access for people on low incomes at risk from natural disaster requires targeted support, such as promoting non-profit “mutual” insurance schemes.

Read more:

Natural disasters increase inequality. Recovery funding may make things worse

Second, only mitigation can bring the overall cost of natural disasters down. Ways to do this include public works (building levees, upgrading stormwater systems, conducting planned burns) and improving buildings (reinforcing garage doors, shuttering windows, managing vegetation around homes, and so on).

The ACCC’s insurance report identifies a range of ways mitigation strategies can be tied into insurance pricing. Yet none of these has been incorporated into the Morrison government’s response to the insurance crisis.

There is little support for the reinsurance pool outside of the federal government. Neither the ACCC, the insurance industry nor community sector advocacy organisations support reinsurance as a meaningful solution.

A reinsurance pool for the whole of Australia?

For the areas of NSW and Queensland now flooded, as well as the rest of the country outside the ambit of the reinsurance pool, the relentless rise in insurance costs will continue, tipping ever more homes out of the insurance safety net.

We must find better solutions to the insurance crisis than what is being offered to northern Australia. A reinsurance pool cannot be a national solution because it isn’t the solution for northern Australia.

There are no cheap and easy solutions, but the terrain is clearly mapped out across an array of inquiries and reports into insurance and climate vulnerability. More than a blanket subsidy for the insurance industry, the time has come for climate vulnerability to be taken seriously by the federal government.

Authors: Antonia Settle, Academic (McKenzie Postdoctoral Research Fellow), The University of Melbourne

A sign of floods present and past in Chinderah, northern NSW, on March 1 2022.

Jason O'Brien/AAP

This won’t do much for those affected by the current floods. It won’t even do much to solve the insurance crisis in northern Australia.

The reinsurance pool, a blunt tool

In the 2021 budget the federal government committed A$10 billion to a cyclone and flood damage reinsurance pool, “to ensure Australians in cyclone-prone areas have access to affordable insurance”. The legislation to establish this pool is now before parliament.

The ostensible rationale is that the government can drive down insurance costs for consumers by stepping in and acting as wholesaler in the reinsurance market, in which insurers insure themselves against the risk of crippling insurance payouts.

The idea is that discounted reinsurance will lead insurers to lower their premiums.

Read more:

A national insurance crisis looms. The Morrison government's $10 billion 'pool' plan won't fix it

There is no guarantee, however, that insurers will pass on their cheaper costs to customers. This means the benefits of the pool are unclear.

So are its costs. Effectively, the government is shifting risk from insurers to itself, subsidising insurance premiums for those in some parts the country from the public purse.

The ACCC inquiry gave considerable attention to the idea of a reinsurance pool. While acknowledging there could be some benefits, it concluded the risks outweigh the rewards:

We do not consider that a reinsurance pool is necessary to address availability issues in northern Australia.

Targeting and mitigating

Above and beyond the aforementioned problems, there are two telling failures of the reinsurance pool plan.

First, subsidising insurance companies doesn’t target help to those who need it most: low-income households.

There is a growing body of research showing that natural disasters, and the ways governments respond to them, is contributing to greater inequality.

As the South Australian Council of Social Service makes clear in a report published this week, improving insurance access for people on low incomes at risk from natural disaster requires targeted support, such as promoting non-profit “mutual” insurance schemes.

Read more:

Natural disasters increase inequality. Recovery funding may make things worse

Second, only mitigation can bring the overall cost of natural disasters down. Ways to do this include public works (building levees, upgrading stormwater systems, conducting planned burns) and improving buildings (reinforcing garage doors, shuttering windows, managing vegetation around homes, and so on).

The ACCC’s insurance report identifies a range of ways mitigation strategies can be tied into insurance pricing. Yet none of these has been incorporated into the Morrison government’s response to the insurance crisis.

There is little support for the reinsurance pool outside of the federal government. Neither the ACCC, the insurance industry nor community sector advocacy organisations support reinsurance as a meaningful solution.

A reinsurance pool for the whole of Australia?

For the areas of NSW and Queensland now flooded, as well as the rest of the country outside the ambit of the reinsurance pool, the relentless rise in insurance costs will continue, tipping ever more homes out of the insurance safety net.

We must find better solutions to the insurance crisis than what is being offered to northern Australia. A reinsurance pool cannot be a national solution because it isn’t the solution for northern Australia.

There are no cheap and easy solutions, but the terrain is clearly mapped out across an array of inquiries and reports into insurance and climate vulnerability. More than a blanket subsidy for the insurance industry, the time has come for climate vulnerability to be taken seriously by the federal government.

Authors: Antonia Settle, Academic (McKenzie Postdoctoral Research Fellow), The University of MelbourneRead more