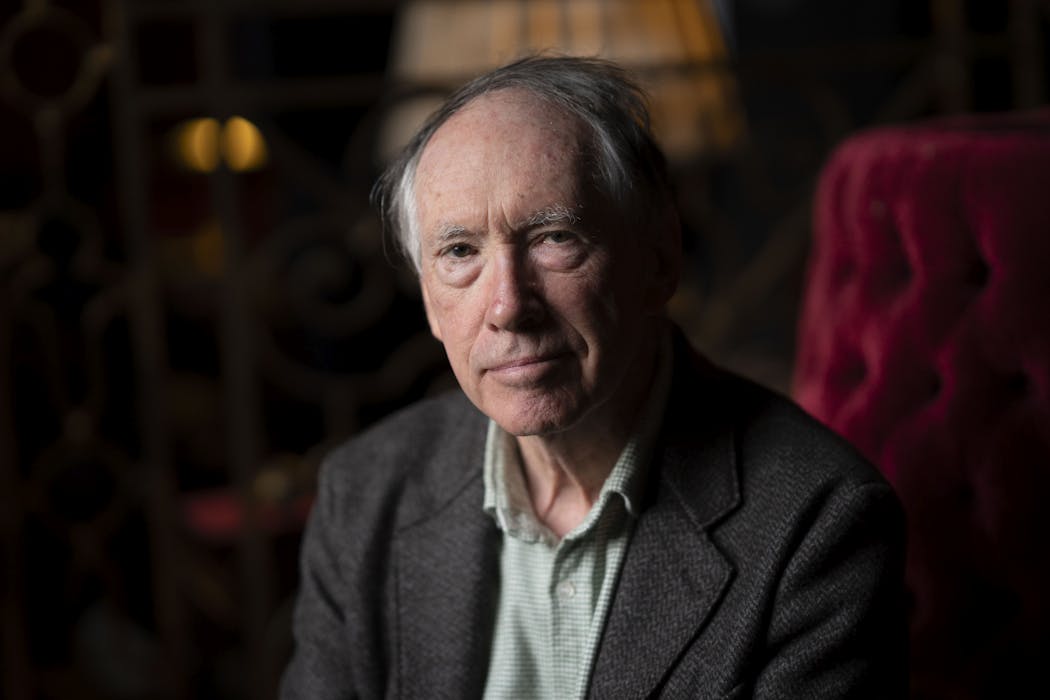

Ian McEwan’s new novel explores resentment and vengeance in a fractured world

- Written by Kevin John Brophy, Emeritus Professor of Creative Writing, The University of Melbourne

Ian McEwan’s new novel, his 18th in a long career of writing books that play with startling premises, bold ideas and big dilemmas, begins as a work of futurist fiction set in 2119. It’s a time when the climate catastrophe has delivered devastating floods to the world and nuclear conflicts have upended world powers.

What We Can Know – Ian McEwan (Penguin Random House)

The United States is a country of heavily armed warlords. Britain is a series of islands with severely limited populations and the centre of world power has shifted to Africa. AI has not, after all, transformed the way the world works because it more or less came to a halt before it got going, thanks to the collapse of populations, the flooding and the wars.

The steady and dour Tom Metcalfe narrates the first half-and-a-bit of the novel. He is an English literature academic (the humanities are still in crisis) and the period he has spent his life researching and teaching is 1990 to 2030. This is possibly one of the dullest literary periods a scholar could choose to devote his life to and one his students increasingly refuse to spend their time on.

Metcalfe is in pursuit of a poem that has disappeared. The poet who wrote it was Francis Blundy – after Seamus Heaney, the most famous poet of this period – and one whose fame reached unimaginable heights when one of his love poems to his wife featured in a Hollywood movie. All drafts of this poem were destroyed by Blundy. Only one copy ever existed, a gift to his wife. The fate of that one copy is unknown in 2119.

Metcalfe spends a lot of time reading the diaries of the poet’s wife, Vivien Blundy, and has confessed to his own lover he is more than half in love with Vivien. He fantasises sometimes that he might have become her husband if he had lived in the period of his research, which he does more or less. It was a time, he keeps reminding us, when food tasted as it should have, when there were still forests you could stroll through, even if species extinctions were already rampant.

The elusive poem might be a masterpiece, one of the most lyrical, insightful and powerful incursions by poetry into the crises of nature ever produced by an English poet. The poem has become famous, especially as an emblem of the Greens protest movement in Britain. This, despite the common knowledge that Bundy was a bullying, climate-change denier.

Searching diligently for this poem, Metcalfe reads and rereads Vivien’s journals – in actual archives and in the digital archive of emails sent. He scours Bundy’s emails, his publisher’s and those of his friends.

It is a little odd that only emails are mentioned as the content of the planet’s digital archive when social media already has exploded far beyond the almost quaint mode of communication known as emailing. In any case we get a good sense of the grind that literary scholarship requires.

But Metcalfe also has a novelist’s impulse in him and he doesn’t mind departing from strict scholarship to recreate the period he is researching.

A poetry reading

Metcalfe recreates for us the second Immortal Dinner. The first Immortal Dinner took place in 1817 at the London home of a well-connected but obscure painter, Benjamin Haydon. The poets Keats and Wordsworth and Shakespeare scholar Charles Lamb were in attendance, among some others. Accounts of the night mention wild drinking, witty and smutty talk, much laughter, and insults taken and forgiven. It became famous in the telling, though it might have been a blur for most of those who were there.

The second (fictional) Immortal Dinner takes place at the Bundy’s country home in October 2014. Friends, family and colleagues gather for the birthday of Vivien and the first reading of a new, major poem written over many months by Blundy especially for his wife.

Authors: Kevin John Brophy, Emeritus Professor of Creative Writing, The University of Melbourne