Nobel-winner Kazuo Ishiguro shows us the illusion of connection with the world

- Written by Jen Webb, Director of the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, University of Canberra

English author Kazuo Ishiguro has won the 2017 Nobel Prize for Literature. For some weeks now, the bookies have been offering odds on the likely winner. Kenya’s Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was front runner earlier this week, followed closely by Japan’s Haruki Murakami. Ishiguro was some way down the list of favourites: a surprise win, no doubt, for the bookies, and one that is likely to generate plenty of discussions and debate.

The commentary about this year’s prize, though, is unlikely to run as hot as it did last year, following the bombshell announcement that Bob Dylan was the new Laureate. With Ishiguro, love him or not, we are unquestionably in the company of a noteworthy writer, one who has been widely honoured. He has been winning literary awards since 1982, when A Pale View of the Hills won the Winifred Holtby Memorial Prize.

Despite this record of success – or perhaps as an inevitable consequence of the current media climate — Ishiguro seems to have been caught unawares by the win. Not unlike Helen Garner’s first response to the email telling her she’d won the Windham-Campbell prize, he thought the announcement of the award was fake news.

This year’s award was based on Ishiguro’s contribution as a writer “who, in novels of great emotional force, has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world”. Sara Danius, Permanent Secretary to the Nobel Academy, added that he is “a writer of great integrity”, one who tackles those complex and enduring themes of “memory, time, and self-delusion”.

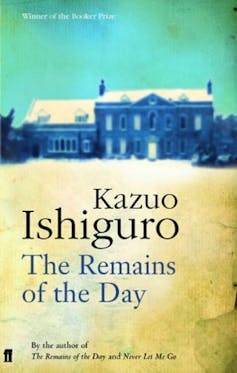

Ishiguro’s 1989 novel The Remains of the Day.

Goodreads

Ishiguro’s 1989 novel The Remains of the Day.

Goodreads

Personally, I’m delighted with the win. Ishiguro’s novels have helped give shape and texture to my life. An Artist of the Floating World (1986; winner of the Costa Book Award) and Remains of the Day (1989; Booker Prize winner) accompanied me through long insomniac nights. The uncertainty, barely-declared unhappiness and sense of dislocation found in both narrators fitted perfectly with my experience of being a stranger in a strange land. When We Were Orphans (2000), with its awkward misfit narrator and its haunting/haunted location, might be considered his least successful book, but I found all that unresolved guilt and unconfirmed identity both compelling and disturbing.

Never Let Me Go was named as Time Magazine’s Book of the Year in 2005. Its exquisite voice, and exquisitely painful dystopia, seemed to fit perfectly the mood of anxiety threading through that decade, one characterised by both late capitalism and the rapidly changing environment associated with the Anthropocene. And, most recently, The Buried Giant (2015) catapulted readers back to post-Arthurian Britain, weaving narrative threads from across history and treating enduring love and failing memory with equal compassion.

Ishiguro is often described as an author who writes across and between genres, moving from speculative fiction, to crime fiction, to social realism and fantasy. However I don’t find it instructive to pigeonhole his books into generic categories.

Ishiguro’s 2005 novel Never Let Me Go.

Goodreads

Ishiguro’s 2005 novel Never Let Me Go.

Goodreads

If anything, his writing demonstrates the permeability of the rules of genre. His technical and literary capacity, along with his closely observed — and coldly if tenderly rendered portraits - locate his writing outside formulae or conventions. The worlds he creates, and the characters that people them, are startlingly authentic - an empty term that I don’t like to use, but which feels right in this context.

Alfred Nobel established the prize, in his will, as one that is designed to reward “the person who shall have produced in the field of literature the most outstanding work in an ideal direction”. “Ideal” is another of those empty terms, but it seems to me that a writer who has consistently tackled problems of ethical relationships, social responsibility, questions of memory, gaps in meaning and identity, and done it all with a light touch and deep empathy fits that bill.

Ishiguro’s characters are often hard to love, but easy to care for, and their struggles with “the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world” offer ways of seeing and thinking about what lies beneath our own feet.

Authors: Jen Webb, Director of the Centre for Creative and Cultural Research, University of Canberra